The SuperBowl’s first hip-hop halftime show was an incredible celebration of blackness– black joy, black creativity, black culture– but it was also a stinging indictment of the framework surrounding that blackness. The show was jammed with layers of meaning, and those meanings deserve to be unpacked and parsed.

Time and Place

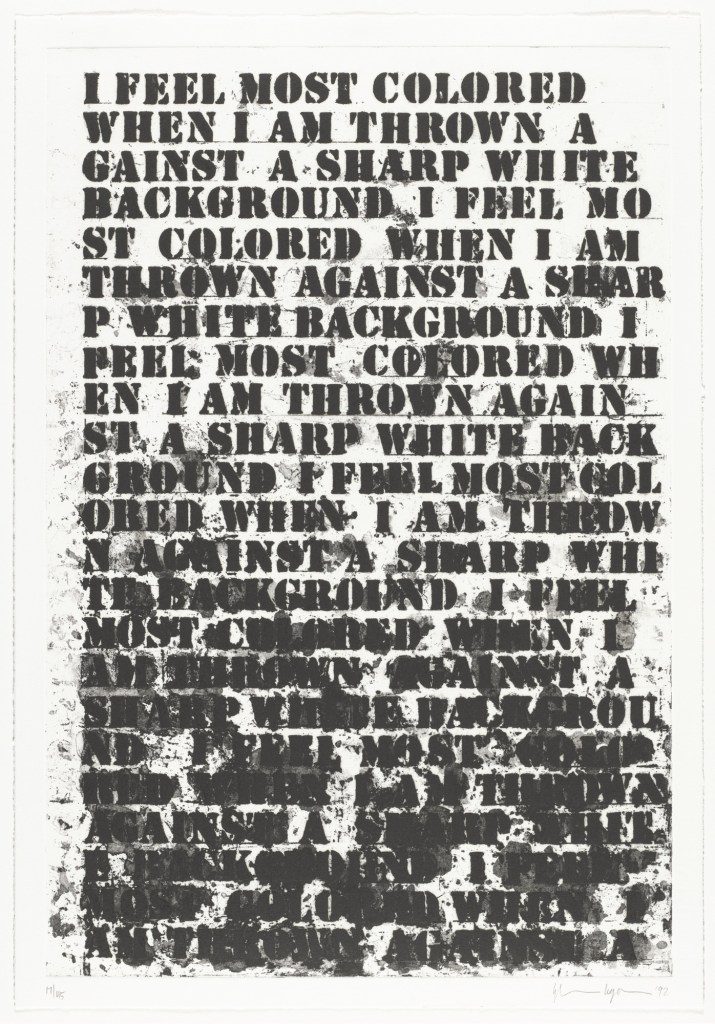

The first thing I noticed about the set was its stark whiteness. It immediately brought to mind the Zora Neale Hurston quote (and the Glenn Ligon piece riffing on that quote): “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.” In contrast to the stark whiteness of the set, the performers’ skin color was on full display; the whiteness enhanced their darkness, emphasizing and celebrating it, rather than hiding from it. But the white set and its literary associations also served as commentary of the SuperBowl as a primarily white space. In fifty-six years of SuperBowls, this was the first time black artists, performing black art forms, was centered. Not only that, but the NFL has a problematic history (to say the least) on issues of race, a notable recent example being the whole “taking a knee” incident (more on that later). The white set placed that white context front and center, acknowledging the historical reality in which the performance was taking place.

Another noteworthy aspect of the set were the buildings it depicted. As others have pointed out, the buildings represented a variety of Compton landmarks: Tam’s Burgers, Dale’s Donuts, the nightclub Eve After Dark… But there were two sides to the buildings: one was a view of them from the outside, while on the other the walls were cut away to reveal the buildings’ interiors. That outside vs. inside dichotomy was an important one, for it enabled an awareness of perspective. The outside view, stark and unadorned as it was, was the view available to outsiders (probably white people) driving through Compton. The inside view, on the other hand, was the one available to those who live and participate in the neighborhood. Unlike the outside view, the inside of the buildings was colorful and vibrant, featuring artwork, texture, movement. The contrast between these two perspectives, outside vs. inside, raised the question: was that vibrant internal life only available to those who live in Compton, or was it simply that outsiders had failed to look in, to see the vibrancy hiding behind our stark preconceptions of the neighborhood?

That question was fully embodied through Eminem, the lone white performer, and his liminal position onstage. He was part of the set, but he was on a roof, not in one of the interior spaces. He was invited in, allowed to create and participate alongside black artists, but the inside of the buildings remained a purely black space. All of the vibrance and creativity that existed in those interiors was proudly and unequivocally black.

Clothing as History and Statement

The costumes, too, were often a celebration of black culture and style. This was especially important since black style has too often been denigrated and looked down on, until white appropriation lets it into the mainstream. There is an unfortunately long history of black style being called “unprofessional,” of clothing and hairstyles being policed as a way of policing black bodies. The Halftime performers, on the other hand, reveled in black fashion.

Snoop Dogg’s blue and gold outfit brought to mind, yet again, the importance of place, since those are the LA colors. That it was a bandana tracksuit also highlighted two trends that have long had a place in black sartorial history. Mary J. Blige’s outfit was patterned to look like a snow leopard, thereby referencing jazz bandleader Cab Calloway’s dramatic style (Vogue); but like Snoop Dogg’s bandana print, leopard print also has a long sartorial history viewers could immediately connect to. Moreover, the leopard spots looked like the squares on disco balls, thus referencing yet another predominantly black musical genre– a genre that, in fact, gave birth to rap and hip hop.

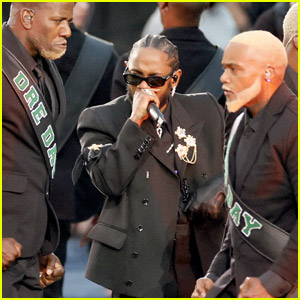

Dr. Dre and 50 Cent’s plain black outfits fit with the Hurston/Ligon concept, the black clothes emphasizing the blackness of the performers, especially in the stark white setting. The black suits worn by Kendrick Lamar and his backup dancers were imbued with more historical and cultural meaning, though. The crisp black suits worn by the lines of black men at angular attention reminded me of Louis Farrakhan and his Nation of Islam bodyguards (a reference very rooted in ’90s LA, like a lot of the Halftime show), but also of Malcom X. The suits were all black, they wore black sashes with green lettering, and their hair and beards were all dyed the same shade of blond: in other words, they wore black, green, and gold, the colors of Pan-Africanism. The colors seemed almost heightened by the fact that they were being worn in February, Black History Month. The only Pan-African color not displayed was red, which traditionally represents blood, either “the noble blood that unites all people of African ancestry” (per Marcus Garvey) or the blood spilled by conquerors and enslavers. Though the red was not on display, blood was very much present in other ways.

Eminem, and the dancers on the ground during his set, all wore hoodies with the hoods up. The backup dancers on the ground were all people of color, though, and Eminem was noticeably white. The hoodies have been a sartorial shorthand for the #BlackLivesMatter movement ever since the shooting of Trayvon Martin. The hoodies made it impossible not to think of Trayvon Martin when Eminem sang, “you only get one shot.” However, that Eminem was a white man in a hoodie prompted the question: in that situation, would he be viewed in the same way as the hooded backup dancers? #BlackLivesMatter was, of course, also centered in Eminem’s set through his much-discussed kneeling, which referred to Colin Kaepernick kneeling during the national anthem at NFL games to raise awareness for the movement. The kneeling prompted a similar question: was Eminem being viewed in the same way as Kaepernick?

Finally, the prison uniforms. The way the prison-industrial complex disproportionately affects people of color is a well-documented fact. Having dancers in prison uniforms amidst this celebration of blackness felt, in some ways, like a simple statement of fact: as they are currently configured, prisons are an inherently black space. Coming after Eminem’s explicitly political number, though, the prison uniforms also read as activism, as a call for prison reform, and for reform of the whole system that funnels people of color into prisons. The issue is especially urgent in the current pandemic, when overcrowding and inadequate healthcare are combining with horrifically fatal results.

There was an evolution, then, in the performers’ clothing, from a celebration of black fashion to overt activist messaging, with Kendrick Lamar’s set, and the way his backup dancers both drew on the history of black fashion and used it as a tool for explicit political speech, as the turning point.

And Yet…

Amidst this exuberant demonstration of black excellence and activism, I did find 50 Cent’s choreography and staging problematic. I understand that it was referencing the original music video, and, as should be clear from the rest of this post, I applaud acknowledgements of history, especially histories that have been sidelined or under-appreciated. But 50 Cent’s Halftime performance was not so much a nod to the original video as a reproduction of it… all of it, including the overly sexualized women grinding all over him. Twenty years have elapsed since In Da Club first appeared, twenty years in which the participation and role of women in rap and hip hop has been discussed, addressed, and in many ways improved. 50 Cent’s set made it look as if #MeToo never happened, R. Kelly’s trial never happened, as if many women hadn’t come forward talking about their mistreatment on music video sets in the 90s and aughts. All of the other artists during the Halftime show updated their staging, so that their music gained new relevance and better reflected the current moment. They managed to raise new issues and questions with their staging; 50 Cent’s, in contrast, felt static.

This is far from an exhaustive analysis of 2022 Halftime show. That’s exactly what made it so great– it was so full of layers and meaning that it’ll take a long time before it’s fully unpacked. I also want to acknowledge my own position as a white woman: I’m far from the ideal person to be unpacking all the references made. But a quick Google of “Halftime 2022” doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface, a surface which is very much worth delving into, which is why I’ve done so. I hope others will do so more, and better, in the future.