A few weeks ago, when discussing how the current pandemic would be remembered, I posited my theory that, at some point, we would start comparing coronavirus to Oklahoma City, Waco, and Ruby Ridge. My thinking was a vaguely mathematical extrapolation: in those days, we were comparing coronavirus to 9/11 (see my last post). Immediately after 9/11, the attacks were being compared to the Oklahoma City bombing (see Marita Sturken’s excellent book on the subject, Tourists of History). If a=b and b=c, then surely a=c, and at some point we would start comparing the coronavirus to the Oklahoma City bombing.

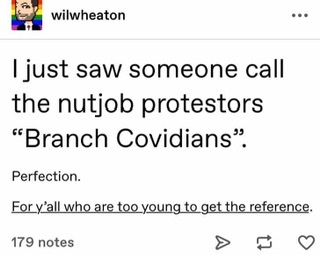

On April 19, NPR published a piece titled, “On 25th Anniversary of Oklahoma City Bombing, Officials Find Lessons for Today.” The piece is an attempt to bring together these fairly disparate traumatic experiences, drawing parallels between the “dehumanization” at the root of both the bombing and the pandemic. On April 20, a friend shared the following image on Facebook:

“For y’all who are too young to get the reference,” the Branch Davidians were a religious sect living on a compound just outside of Waco, Texas, which was besieged by the ATF and FBI in 1993. Waco was a thorny, murky muddle of political issues– the Second Amendment, the right to property, individual liberty, the limits of federal power… Waco was also cited by Timothy McVeigh, one of the Oklahoma City bombers, as the impetus for his attack. The reference to “Branch Covidians” is thus a similar move to NPR’s, drawing parallels between those earlier related events and the current coronavirus.

“For y’all who are too young to get the reference,” the Branch Davidians were a religious sect living on a compound just outside of Waco, Texas, which was besieged by the ATF and FBI in 1993. Waco was a thorny, murky muddle of political issues– the Second Amendment, the right to property, individual liberty, the limits of federal power… Waco was also cited by Timothy McVeigh, one of the Oklahoma City bombers, as the impetus for his attack. The reference to “Branch Covidians” is thus a similar move to NPR’s, drawing parallels between those earlier related events and the current coronavirus.

Whereas the previous logic of my hypothesis was more mathematical, and while I am wary of drawing comparisons between events (like Sontag, who warned that our understanding of disease gets obscured and influenced by our metaphors for those disease, I fear that comparisons will obscure and influence our perceptions and understandings of the pandemic), as the weeks and social distancing have dragged on, the more I see this particular comparison as an apt one. More than simple geographic proximity, such as New York being the epicenter of both 9/11 and the coronavirus, the same ethical and political issues seem to be at play in Waco/Oklahoma City and our current moment.

In late March, for example, as the pandemic was starting to spread throughout the US and states were beginning to issue shelter-in-place orders, there was a run on guns and ammunition, with many people rushing to stockpile before going into isolation. There was also debate about whether gun stores were considered “essential businesses” and whether they should be allowed to remain open during the pandemic in the way that groceries, pharmacies, and the like were. The Second Amendment, and the question of how many, and what kinds of, guns people are allowed to own was also at issue in the early ’90s in the cases of Ruby Ridge, Waco, and Oklahoma City. In all those cases, too, the Second Amendment was tied up with a dark element of white nationalism, specifically Christian white supremacy. So too this current moment, with white nationalists exploiting the chaos of the coronavirus to promote conspiracy theories online and to foment plans for mass destruction (one white supremacist was arrested for planning to bomb a hospital treating coronavirus patients, while others have been discussing plans online to “weaponize” coronavirus). Christian fundamentalism is also playing a huge role in the spread of the coronavirus– Liberty University, an Evangelical school, is one of the only schools that reopened after shelter-in-place orders were issued, allowing for coronavirus to spread among its student population. Evangelical leaders were also the ones who encouraged President Trump to downplay the threat of the virus, leading to delays in federal response and increased spread of the virus at the beginning of the year.

And of course, in all these cases is the question of individual versus collective liberty. Can the government compel us to leave our homes, as they did at Ruby Ridge and Waco? Can it compel us to stay in our homes, as it’s doing now with the coronavirus? The “Branch Covidians” that Facebook post referred to are protesting lockdown orders, arguing that it’s un-American to force someone to stay indoors if they don’t want to.

Despite my wariness of drawing comparisons, I think there’s an important point to be made about the particular kind of home-grown American anger at work in all these cases. It’s a fury directed at the federal government, fueled by white supremacy and Christian fundamentalism, that finds its expression in moments of perceived government overreach. Though Ruby Ridge, Waco, and Oklahoma City have largely been relegated to footnotes in our national history, overshadowed by the events of 9/11, I think they continue to have an enormous impact on our collective psyche, especially since the issues at their root were never, in fact, resolved. Second Amendment rights continue to be debated today, as is religious freedom. Far from being a distinctly separate event, I would even argue that our response to the coronavirus is an extension of our response to Ruby Ridge, Waco, and Oklahoma City, a continuation of that unresolved and ongoing debate. Thinking of the pandemic in those terms may illuminate how we should respond to it, and of the dangers it presents that we may not even yet be aware of.